Creating animated data visualisations with Plotly & Pandas

Table of Contents

Tools for creating data visualisations

The primary focus of this blog post will be to show you some examples of how to create data visualisations with python, through the use of various libraries. However, before we get to that I want to provide a high level introduction to some of the applicatiosn and libraries that are most commonly used to create data visualisations within the industry.

Power BI

An example Power BI dashboard by Microsoft

Power BI is Microsofts solution to data visualisation made up of a collection of services, apps, and connectors, that combine together to turn various data sources into unique data visualisations. Some notable names that use Power BI are KPMG, EY, PWC, Heathrow Airport, Nokia, and HP, just to name a few.

Tableau

An example of a Tableau dashboard by Tableau

Tableau is the data visualisation arm of Salesforce, that allows for querying relational databases, analytical processing cubes, cloud databases, as well as simple spreadsheets, in order to create graph style data visualisations. On top of this, it also provides the ability to store data in it’s own in memory data engine. Some notable names that use Tableau are Zoom, Lockhead Martin, and Macy’s.

Qlik Sense

An example QlikSense dashboard by QlikSense

Qlik Sense is a data visualisation tool offered by Qlik, a business analytics platform. While not as large as the previous two entries, it is used by companies such as Johnson & Johnson, Raytheon Technologies, and Danone.

Looker

An example Looker dashboard created by DataFlix

Looker is a business intelligence option provided by Google, and is part of their Google Cloud Platform. Some companies that currently use Looker are Roku, Walmart, and Experian.

Python Libraries

An example of a Dash web dashboard created by Plotly

In terms of open source, python has a number of libraries that support data visualisation. They range from libraries such as MatPlotLib, Plotly, Seaborn, GGplot, and GeoPlotLib, just to name a few. While each library has it’s own unique advantages and disadvantages, this blog post will mainly focus on using MatPlotLib and Plotly, in combination with some other data tools such as Pandas.

The image above is an example of a dashboard created via Plotlys Dash framework, which is designed to allow for the easy creation of web based data visualisations and dashboards.

Now that you have a brief understanding of the range of the tools available for creating data visualisations, let’s take a deeper dive into how to create some visualisations in Python.

Introduction to data visualisation with Python

Environment setup

The first thing to do before we jump into our sample projects, is to make sure we have our development environment set up. While there are numerous ways you can go about this, these are the main requirements - Python 3, MatPlotLib, Plotly, and Pandas.

The IDE environment that I will be using is Sublime Text with the Anaconda package to enable it to be a full python IDE.

Rather than waste blog space by writing out installation instructions for the required tools and libraries, please see below for linked installation guides for each of the aforementioned requirements. All links direct you to official documentation or installation guides for one of the requirements. If you prefer to Google for other 3rdsup> party installation guides, please feel free to do so.

Disclaimer

The following projects will presume you have an understanding of coding, and can grasp the basic concepts of syntax and understand the slight nuances involved with python (as a lightly typed language) as compared to a language like Java.

Sample project #1

Video Summary

This first project is the most basic, and consists of creating a simple line graph & scatter plot to show the squares of 5 different numbers. Follow along with me via the video above, or teh written tutorial below, as I introduce some basic concepts and controls.

Each code block below is a part of the overall script file. A download link to the complete script file will be provided at the bottom of the project section.

The first step is to import the library we will be using to create our line graph. In this case it’s the pyplot sub library of the matplotlib python library.

import matplotlib.pyplot as pyplot

Since this example is designed to plot the squares of a set of values, we will naturally have to declare both the base values, and the sqaure values themselves. So let’s declare them as values in two separate arrays. The first is the base values, while the second is the squares of the base values.

values = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

squares = [1, 4, 9, 16, 25]

Next we have to start creating our graph. In my case I decided to change the style of the graph so that it wouldn’t blind me at night by having a light background. To do this, we need to know what styles are available to us. Since sublime doesn’t really like running some code and outputting it because it isn’t a command line interface, you may have to open up a terminal and run the following code.

python

import matplotlib.pyplot as pyplot

pyplot.style.available

These three lines of code should print out an array of all available pyplot styles. See below for the output:

['Solarize_Light2', '_classic_test_patch', '_mpl-gallery', '_mpl-gallery-nogrid', 'bmh', 'classic', 'dark_background', 'fast', 'fivethirtyeight', 'ggplot', 'grayscale', 'seaborn', 'seaborn-bright', 'seaborn-colorblind', 'seaborn-dark', 'seaborn-dark-palette', 'seaborn-darkgrid', 'seaborn-deep', 'seaborn-muted', 'seaborn-notebook', 'seaborn-paper', 'seaborn-pastel', 'seaborn-poster', 'seaborn-talk', 'seaborn-ticks', 'seaborn-white', 'seaborn-whitegrid', 'tableau-colorblind10']

As you can see, by default there are quick a few styles available, but they’re not necessarily very descriptive, which you can see for yourself by trying different styles once we’ve finished this sample project. Instead you can refer to this style sheet reference guide provided by matplotlib to see what each style will look like.

Note: You must change the style before you add or call any functions on pyplot otherwise the style won’t be used correctly.

Our next step is to declare and create a common layout of subplots and the encompasing figure by calling the subplots method. This method returns two objects, a figure and an array of axes. To keep things simple, we’ll call these figure, and axes, respectively.

Note: an alternative to using calling subplots() is to use two individual method calls pyplot.figure() and figure.add_subplot(111).

Finally since we wish to use the data in the arrays we declared earlier, we will call the plot method on the axes arrays, and provide it with values for the x-axis, the y-axis, and declare any supplementary style options.

The first argument is the array of values for the x-axis, the second is the array of values for the y-axis, and the third argument tells plotly to use a linewidth of 4 in the resultant graph.

pyplot.style.use('dark_background')

figure, axes = pyplot.subplots()

axes.plot(values, squares, linewidth=4)

Now that we’ve added values, and styled the basics of our graph, we can move on to styling other key aspects of our data visualisation. Mainly we will look at declaring a title, labels for each axis, and styling the labels for each data point.

Finally we will call two methods, one that will display the graph on screen, and another that will save the graph straight to a png file. The savefig method has multiple optional arguments, in this case I’ve made the image transparent so that it doesn’t clash with the blog post theme, and told plotly to keep the image as tight to the graph as possible while adding in 0.1 inches of padding around the entire graph.

axes.set_title("Square numbers", fontsize=30)

axes.set_xlabel("Value", fontsize=18)

axes.set_ylabel("Sqaure of Value", fontsize=18)

axes.tick_params(axis='both', labelsize=18)

pyplot.show()

pyplot.savefig('linegraph_1.png', bbox_inches='tight', pad_inches=0.1, transparent=True)

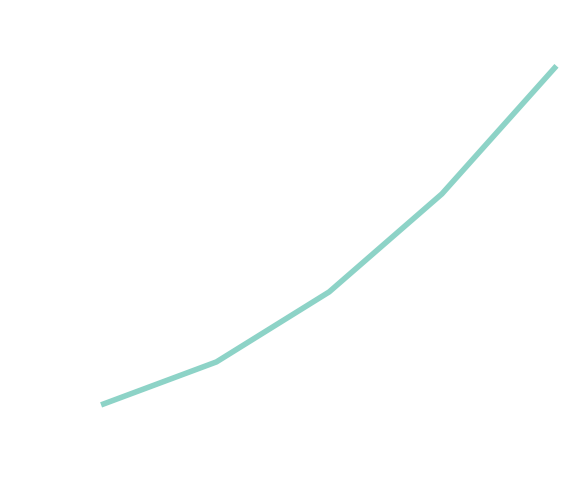

This is what your resultant graph should look like:

The full python script file is available here

Sample Project #1.2

It’s time to build upon the basics we’ve just learnt, and expand our repertoire of graphs by creating a scatter plot using the same dataset. Follow along with the code below to see what changes we need to make, and how things differ slightly in the setup for a scatter plot.

In this section I won’t reintroduce any code that has stayed the same, so if you’re following along this will be a good practice to see if you grasped some of the basic concepts from the first sample. Feel free to modify the code as you wish, perhaps by adding more data points, or changing the type of data the graph will represent.

As you can see it only takes changing a single line of code to have plotly generate a scatter plot, instead of a line graph. In this case instead of calling the subplots method, we call the scatter method. The only difference between these two method calls is the third argument. In subplots we told plotly the width of the line on the graph, with scatter we tell plotly the size of each individual point within the scatter plot.

# ...

axes.scatter(values, squares, s=100)

# ...

With our changes, this is how the scatter plot should look:

Sample Project #1.3

Now that we’ve figured out how to generate a scatter plot, we’re going to up the difficulty by using python to generate a random set of values, use some additional optional arguments to style the resultant scatter plot, and manually modify the axis range.

To do this we will use the range function within python to generate a sequence of numbers between 1 and 1000 and store them in an array.

We will then use a the python equivolent of a for each loop to calculate the square of each of the newly generated numbers.

Once we have our new dataset, we will add a new optional argument to the scatter method call, which tells pyplot to override the base style colour for each point within the graph with the specified value. I’ve also reduced the size of each point so that it’s slightly easier to view.

Finally, we will tell pyplot the specific range of each axis by declaring the starting point of the x-axis, the end value of the x-axis, the starting point of the y-axis, and finally the end value of the y-axis.

values = range(1, 1001)

squares = [x**2 for x in values]

# ...

axes.scatter(values, squares, c='green', s=10)

# ...

axes.axis([0, 1100, 0, 1100000])

# ...

If everything went to plan, this is what your resultant scatter plot should look like:

The resulting scatter plot of square numbers with our new dataset Note: as you can see, the sheer number of data points makes our scatter plot resemble a line graph, however if you look closely you can notice that the line isn’t smooth in some places.

Sample Project #1.4

While we’re looking at ways to change the look and feel of our graphs in Pyplot, let’s take a quick look at some of the other style options we have available to us.

The optional “c” argument tells Pyplot which axis value we wish to base our colour selections on. While the “cmap” argument tells Pyplot which colour map to use. In this case I’ve used the viridis colour map, to see what other options are out there, take a look at this reference sheet

# ...

axes.scatter(values, squares, c=squares, cmap=pyplot.cm.viridis, s=10)

# ...

Using a colour map should result in a scatter plot that looks something a bit like this:

The resulting scatter plot of square numbers with our new colour map

The full python script file for the scatter plots is available here

Small things like using a colour map, or changing the style of the graph can help get the core meaning of the dataset across to your users more easily.

Sample project #2

Video Summary

The second project builds upon the first, and consists of generating a dataset that represents a random walk in an open area, and maps the data via a scatter plot to provide a visual representation of the dataset. Follow along with me via the video above, or the written tutorial below, as I introduce some more basic concepts and controls.

For this project we’ll delve into a couple of new concepts - Classes, random dataset generation, and adding specific unique points.

To start off with, we will take a look at the class that will be responsible for generating all our “steps” within a walk. These will be randomly chosen from a list of potential options we provide within the fill_walk method.

Firstly we will need to import the choice module from the random library. This allows python to select psuedo-randomly from an array of options we provide.

Next we will define the class, and the standard init method, think generic constructor if you’re familiar with Java. In this case we provide a default value for num_points, but this can be overriden by providing an argument when calling the constructor method. In the constructor we will also initialise two arrays, those for the x co-ordinates of our steps, and one for the y co-ordinates.

from random import choice

class RandomWalk:

# A class to generate random walks.

def __init__(self, num_points=5000):

# Initialize attributes of a walk.

# num_points can be defined in the initial call, or defaults to 5,000

self.num_points = num_points

# All walks start at (0, 0).

self.x_values = [0]

self.y_values = [0]

Now that we have a basic class defined, let’s look at the most important method, the one that will actually generate the steps for our walk. To do this we define a method called fill_walk, and supply it with the object itself so that it can make changes to it’s own data.

The first step is to make sure all our logic is wrapped in a loop so that it keeps running until we reach our desired number of step, which is controlled by the num_points variable. Please read the following warning before moving on, as it is a key concept that must be understood in order to be successful with python.

Note: Unlike Java, it is important to keep track of how you’re indenting your code, as python uses indentation in place of curly braces {}. Not being consistant with your indentation, including the use of indent characters vs spaces, can cause some surprises when it comes to running the code at the end.

So now that we have a loop that will run until we reach our intended number of steps, we can start letting python make some pseudo-random decisions for us.

Keeping in mind that our steps will be graphed we need to come up with a way of translating concepts like distance, and direction, into a co-ordinate system. In this case, we use the logical solution of assigning the value of +1 to turning right, since graphs usually have positive numbers on the right and negative numbers on the left.

Now one might expect us to do something similar for the distance, however since each step is merely a difference in co-ordinates from the last step, we can use a trick of multiplying the distance by the direction, which will either give us a negative number for a step of x distance to the left, or a positive number for a step of x distance to the right.

Now that we have a system that works for moving left and right, we can duplicate this logic for movement forward and backwards.

Have some fun with this bit, if you wish to have half turns add in decimal options. If you wish to only have short distances or long distances then change the arrays as desired. Since this is all pseudo-randomly generated, no two walks will be exactly the same.

def fill_walk(self):

# Calculate all the points in the walk.

# Keep taking steps until the walk reaches the desired length.

while len(self.x_values) < self.num_points:

# Decide which direction to go and how far to go in that direction.

x_direction = choice([1, -1])

x_distance = choice([0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10])

x_step = x_direction * x_distance

y_direction = choice([1, -1])

y_distance = choice([0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10])

y_step = y_direction * y_distance

So we’ve provided python with some steps, let’s cut a corner and just skip to the next step if the distance was 0. Naturally we could remove the option in the distance choice arrays if we didn’t want a 0 distance as an option.

Once we’ve calculated the distance and direction of our steps, let’s figure out what the final co-ordinates of our step will be, using the co-ordinates of our last step as the starting point. This is simply a case of addition, as remember if we moved to the left and backwards, we would have a negative number.

Once we’ve calculated the x and y co-ordinates of our current step, we can add these to the arrays of x and y values.

# Reject moves that go nowhere.

if x_step == 0 and y_step == 0:

continue

# Calculate the new position.

x = self.x_values[-1] + x_step

y = self.y_values[-1] + y_step

self.x_values.append(x)

self.y_values.append(y)

And there we go, you should have a class that can generate random co-ordinates that start from the previous co-ordinates, and have various ways to have fun with it.

Now that we’ve coded the ability to generate a random data set, let’s look at how we can use this data to generate a data visualisation of our walk.

Just like in previous examples, we need to import the pyplot library as this is what we’ll be using to create our scatter plot.

It should be obvious that if we wish to graph a random walk, then we must actually make use of our newly created class and put it to work. So declare a variable to hold the random walk object, and then call the fill_walk method.

import matplotlib.pyplot as pyplot

# Generate a new walk with the default number of steps.

generatedWalk = RandomWalk()

# Fill the x and y values with an array of "steps"

generatedWalk.fill_walk()

All the code to this point is merely the data, if you don’t care about that then hopefully you just skipped ahead for this part, it should look familiar if you read through sample projects #1 - #1.4.

As is usual for me, I’ll use the dark_background, create placeholders for the figure and axes, and then generate the scatter plot with our newly generated random data.

# Choose the Pyplot style

pyplot.style.use('dark_background')

# Plot the points in the walk.

figure, axes = pyplot.subplots()

# Generate the scatter plot

axes.scatter(generatedWalk.x_values, generatedWalk.y_values, s=15)

pyplot.show()

pyplot.savefig('walk_visualised_1.png', bbox_inches='tight',

pad_inches=0.1, transparent=True)

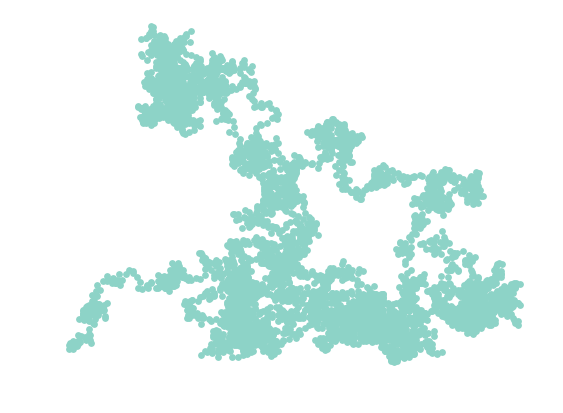

As you can see, the resultant graph is confusing, and really wasn’t worth the time we spent writing the RandomWalk class.

Sample project #2.1

Now that last graph was a bit disappointing. It wasn’t clearly understandable, and the look of the scatter plot didn’t aid in understanding the meaning of the data either. So let’s change that.

Now let’s imagine we have a walk that’s lasted 100,000 steps. I know that might seem crazy, but the bigger our data set the easier it is to visualise some of the concepts I’m talking about, so bear with me.

We will essentiall use the same code as the previous example, but with a few slight modifications that will provide much needed understanding.

To start let’s make sure our resultant graph will have enough clarity so that we can see it clearly. To do this we add some optional argumentes to the subplots method call. The figsize argument is the size of the figure in inches, while the dpi argument is the level of detail in the figure.

Note: The higher these numbers are, the bigger the graph will be both in visual size, and file size.

# Generate a walk with a step count of 100,000

generatedWalk = RandomWalk(100_000)

# Fill the x and y values with an array of "steps"

generatedWalk.fill_walk()

# Choose the Pyplot style

pyplot.style.use('dark_background')

# Plot the points in the walk.

# Define the size of the figure in inches, and the DPI of the resultant figure.

figure, axes = pyplot.subplots(figsize=(15, 15), dpi=600)

Now that we’ve made sure our graph will be legible, let’s try and extract some meaning from our data. I don’t know about you, but I never teleport across the city while I’m on a walk, no matter how much I wish I could. So since walks have a linear progression, from start to end, let’s create an sequence of numbers from start to finish, that we will use to assign meaning to our co-ordinates. To do this we can use the same range function we used in some of our earlier examples.

# Generate a sequence to be used to define the first step through to the last step.

walk_order = range(generatedWalk.num_points)

Okay, so now we have an order to our steps, but how exactly is that going to help us? Well if you remember, we can use a colour map to change the colour of points on a scatter plot according to where they occur in the overall sequence, however unlike our previous examples, we’re not going to base this order off of any of the co-ordinates, since the walk can go up, down, left, right, and as such if we start at 0,0 but in 5,000 steps end up back at 0,1 then the 0,1 would be considered the second point in the colour map. So let’s use our recently create walk_order, this is a sequence of numbers starting at 1 and ending at same number as num_points.

# Generate the scatter plot

axes.scatter(generatedWalk.x_values, generatedWalk.y_values, c=walk_order, cmap=pyplot.cm.coolwarm, edgecolors='none', s=0.5)

What we’ve just done is assign each step a colour, and the further along in the walk that step is the further along in the colour map we’ll go. In this case I chose a colour map that starts with blue and ends with red, so early steps will be dark blue, steps in the middle will be white, and steps near the end will be a dark red.

While this alone provides some much needed meaning to our data, it would probably be easier if we could easily identify the starting point and end point of the walk without having to judge shades of colours. Pyplot lets us do this, by specifying specific co-ordinates to map, and as with any other point we can assign them a colour.

Our RandomWalk class declared that we start at 0,0 so let’s add a point at 0,0 on our graph, make it slightly larger than the rest for easy identification, and make it green. Green always means go right?

Similarly, we can do the same thing but with the end point. This time we’ll make it red, and extract the very last x and y co-ordinates from our generatedWalk dataset.

Note: Use existing pre-conceptions with your data visualisations, there’s no need to re-invent the wheel when everyone already knows that green means go and red means stop.

# Define a specific point as the starting point

axes.scatter(0,0, c='green', edgecolors='none', s=50)

# Define a specific point as the end point

axes.scatter(generatedWalk.x_values[-1], generatedWalk.y_values[-1], c='red', edgecolors='none', s=50)

There’s not much left to do, other than remove the axes so they’re not visible, after all this is a walk and we don’t exist in a 2D cartesian plane. After that, the only thing left to do is display our work, and save the graph for later reference.

# Make the axes invisible since they are merely co-ordinates and have no real meaning.

axes.get_xaxis().set_visible(False)

axes.get_yaxis().set_visible(False)

pyplot.show()

pyplot.savefig('walk_visualised_2.png', bbox_inches='tight',

pad_inches=0.1, transparent=True)

If you followed along, you should see something like the scatter plot below.

The resulting scatter plot of our random walk Remember that our walks are psuedo-randomly generated, so every time you run the above code you’ll end up with a new walk path. In fact here’s a second walk that I visualised with a different colour map. Which do you prefer?

The resulting scatter plot of our random walk

I’m not sure about you, but the addition of the start and end points, along with the use of a colour map definitely make it easier for me to follow the route, even if it’s not foolproof.

The full python script file for the random walk scatter plots is available here

Sample project #3

Video Summary

The final project is the most complex, and jumps from introduction to full on use of Plotly and Pandas to create a real world example of what these tools can offer. Follow along with me via the video above, or the written tutorial below, as I introduce these more advanced ideas.

This is where data visualisation meets the real world. If you read my first blog post, we talked about leveraging data visualistion to bring easy understanding by our audience to data sets, and with the power of tools such as Plotly Express, and Pandas we can do just that.

Note: The following example is not for the faint of heart, it will drive you mad, and it will require a painstaking amount of dedication to getting things right.

All the other sample projects in this blog post were basic introduction style stuff, with this final sample project I’m throwing you in at the deep end. While I will do my best to explain the code and provide the sources I used to create it, I won’t be explaining every little nuance and caveat contained within.

Afterall I have to leave you with something to do, and questions are a good starting point for any learning journey.

Shoutout to Rachel Lund for publishing a guide to plotting CSV data with python and Plotly on medium.com/Analytics Vidhya. Take a look at the article here

Disclaimer: Due to the length and scope of this example, I will be adopting a bullet point format to identify each step, and will provide paragraph style explanations where necessary.

What exactly are we doing?

I almost forgot, this is probably a good time to actually talk about what this sample project will be. A key visualisation in my first blog post was the idea of using a geographical bubble map to convey Covid-19 case data. Since most countries kept a list of new cases per day, and not just cumulative totals, our job in this example is to create an animated geographical bubble map that shows the number of new cases per day, per continent. Our data visualistion should start in January 2020, and continue until we reach the latest numbers.

You heard me right, we’re jumping from a scatter plot with pretty colours, to an animated bubble map with a dataset spanning almost 18 months. Reader meet the deep end. Deep end be kind to the reader.

And we’re off …

Step 1: import pandas, plotly.graph_objects, and plotly.express

Pandas is a useful data manipulation library that we will use to make changes to our source data as needed through this example. Graph_objects are used to contain all the information we’ll need to create an animated bubble map. Finally, Express is a useful subset of the Plotly library that makes it significantly easier to create detailed data visualisations, such as geographical bubble maps.

import pandas as pandas

import plotly.graph_objects as graphObject

import plotly.express as express

Step 2: Shamelessly borrow a bit of code to create a function that will allow us to check a dataset in it’s entirety rather than just a sneak peak at a portion of it.

Hey, who said software developers always right original code. The best kept secret is that software developers get paid to know what code they can copy, how to use it, and even more fundamentally - understand the code so you’re not using it blindly.

Check out the stack overflow thread that provided this handy little function here

def print_full(x):

pandas.set_option('display.max_rows', None)

pandas.set_option('display.max_columns', None)

pandas.set_option('display.width', 2000)

pandas.set_option('display.float_format', '{:20,.2f}'.format)

pandas.set_option('display.max_colwidth', None)

print(x)

pandas.reset_option('display.max_rows')

pandas.reset_option('display.max_columns')

pandas.reset_option('display.width')

pandas.reset_option('display.float_format')

pandas.reset_option('display.max_colwidth')

Step 3: Find a datasource that provides us with the data we need, in a format that will work for what we need it to do.

I spent 2 long years of my life being the go-to man when it came down to Extracting, Transforming, and Loading datasets. That’s right, I spent two years as an ETL developer, and it wasn’t always fun, but it has given me a greater understanding of what to look for when it comes to datasets, and judging the amount of work it will take to get them to a point where they’re useable for the task at hand.

Since I spent 2 years doing that, and this is supposed to be a guided tutorial, I shall just go ahead and provide a link to the datasource that I used. If you wish to take on this example with your own dataset so you can get a better grasp on the ETL process, then by all means go ahead.

Thanks a lot to the WHO for providing global Covid-19 data in a handy CSV format here

Note: I prefer to work with local data files when I can because then I control the data, I don’t have to worry about a company or person changing the format, layout, or contents while I’m actively programming something. If you wish to grab the data directly from a source, just replace the local URL with the URL to the desired dataset in CSV format.

Pro Tip: Always, ALWAYS, ALWAYS check the data you’re importing to see if it matches with what you’re expecting from the source. If you don’t you can waste hours of effort.

sourceData = pandas.read_csv("..//WHO-COVID-19-global-data.csv")

print_full(sourceData.head())

print_full(sourceData.info())

Step 4: Start the transformation process

Did I mention you should always check the data you’re importing? Because if you skipped that step, you wouldn’t have seen that the dates aren’t being read as datetime, which is something that will make our life infinitely easier down the road. So let’s go ahead and convert that column so we don’t run in to issues later on.

Naturally we’re going to double check that our changes carried through, and our data is now of the right type.

sourceData['Date_reported'] = pandas.to_datetime(sourceData['Date_reported'], dayfirst=True)

sourceData.sort_values(by=['Date_reported', 'WHO_region'], ascending=True, inplace=True).reindex()

print_full(sourceData.info())

Step 5: Find supplemental information needed to reach our goal.

If you remember, our goal is to create a data visualisation that shows the number of new cases per day, per continent. If you’ve also been following along, you’ll know that the WHO data doesn’t exactly provide a continent column, so we’re going to have to add it ourselves. To do this we’re going to find a table that contains a column we can use to join the continents to each row in the WHO table, just like this one

Note: while I have done my best to verify the integrity of the data within the continents CSV file, I cannot guarantee it as it is from an unkown 3rdsup> party.

Challenge: Find an alternate data source, and use that to get the information we need. In this case the continent each country is located in.

Okay so we have our dataset that will give us the continents, but we still need to somehow add it to our dataset so it’s actually useable. Luckily Pandas gives us a way to merge two data sources together, and the syntax is pretty straight forward. If you have any questions about it, I suggest you check out the official documentation here.

Reminder: This is the last time I’ll tell you to double check your data, from here on in it’s up to you to remember, or recognise that I use the print_full function for a reason.

continentalIndex = pandas.read_csv("../continents.csv")

sourceData = pandas.merge(sourceData,

continentalIndex[['Continent_Name', 'Two_Letter_Country_Code']].drop_duplicates('Two_Letter_Country_Code'),

how='left',

left_on='Country_code',

right_on='Two_Letter_Country_Code')

print_full(sourceData.info())

Step 6: Create a colour map so our bubble map looks pretty.

This step probably doesn’t need any explanations, but if you need help Google “python dictionaries”.

colour_map = {"Asia": "royalblue",

"Europe": "crimson",

"Africa": "lightseagreen",

"Oceania": "orange",

"North America": "gold",

"South America": 'mediumslateblue'

}

Step 7: Transform the amalgam of data into something that only contains what we need it to.

Okay here’s the downside to data visualisation, and data handling in general - Transformation.

So we have a massive table, that now has the data we need, but not in a format that’s useful to us. If you think of what we want out of this whole process, we’re going to need 3 key things. The date of each slice of data, the continent it references, and the number of cases for that continent on that day.

Sure you could do it manually, but please don’t, you’ll make one mistake 90 minutes in and end up giving up or cursing like a sailor who’s just had their rum ration cut in half.

Once again Pandas provides some useful tools we can use to transform our original data set into a new dataset that is nearly perfect for our uses. I am of course talking about the groupby, and agg functions.

By combining these two functions we can group our data by specific columns, or combinations of columns. For our example we’re going to group by the date, and the continent since we really only want one entry per continent per day. We will combine this with the agg function, which provides a means to aggregate, or combine, all the data that would otherwise be lost when we grouped our original data by our two chosen columns.

Challenge: Choose a different statistic to model, perhaps deaths per day, or maybe total cases per day up to the date in question.

# code to aggregate from : https://stackoverflow.com/questions/40553002/pandas-group-by-two-columns-to-get-sum-of-another-column

continental_data = sourceData.groupby(by=['Date_reported', 'Continent_Name']).agg({'New_cases': "sum"}).reset_index()

print_full(continental_data.head())

Step 8: Keep transforming that data, there’s a bit more we need to do in order to fufill all our requirements.

Now I know this will look quite silly, but trust me, we really do need a way to label each day in our final animation, so let’s go ahead and transform all the dates back into strings so we can use them later without having to worry about converting them.

Note: We only need one label per day, so let’s extract unique days into it’s own variable for later use.

unique_dates = continental_data['Date_reported'][continental_data['Date_reported'] > pandas.to_datetime('03/01/2020')].sort_values(ascending=True).unique()

datesAsStrings = [pandas.to_datetime(str(x)).strftime('%d %b %y') for x in unique_dates]

continental_data['date'] = [pandas.to_datetime(str(x)).strftime('%d %b %y') for x in continental_data['Date_reported']]

Step 9: Keep transforming.

At this point I feel like an autobot, doing nothing but transforming one way, then transforming back again, but this is what needs done if we want a data visualisation that’s useful at the end of the day.

Enough humour, back to the serious task of data handling.

Now something to keep in mind is that the developers of Plotly are lazy. Rather than continue to expand the built-in latitude/longitude dictionaries, they stopped after adding in the U.S. States and instead provided the means for graphing directly via geoJSON or latitude/longitude pairs.

If you’ve been paying attention, you’ll know that we don’t have the latitude and longitude for each continent. So we’re going to have to get that data, and add it to our dataset. Unfortunately I couldn’t find a csv that contained this information, at least not within the first 10 results of my google search, and honestly I got bored after that.

So instead I used TravelMath.com to find the co-ordinates for each continent.

continental_data['latitude'] = 0

continental_data['longitude'] = 0

continental_data.loc[continental_data['Continent_Name'] == 'Africa', 'latitude'] = 7.18805555556

continental_data.loc[continental_data['Continent_Name'] == 'Africa', 'longitude'] = 21.0936111111

continental_data.loc[continental_data['Continent_Name'] == 'Europe', 'latitude'] = 48.6908333333

continental_data.loc[continental_data['Continent_Name'] == 'Europe', 'longitude'] = 9.14055555556

continental_data.loc[continental_data['Continent_Name'] == 'Asia', 'latitude'] = 29.8405555556

continental_data.loc[continental_data['Continent_Name'] == 'Asia', 'longitude'] = 89.2966666667

continental_data.loc[continental_data['Continent_Name'] == 'Oceania', 'latitude'] = -18.3127777778

continental_data.loc[continental_data['Continent_Name'] == 'Oceania', 'longitude'] = 138.515555556

continental_data.loc[continental_data['Continent_Name'] == 'North America', 'latitude'] = 46.0730555556

continental_data.loc[continental_data['Continent_Name'] == 'North America', 'longitude'] = -100.546666667

continental_data.loc[continental_data['Continent_Name'] == 'South America', 'latitude'] = -14.6047222222

continental_data.loc[continental_data['Continent_Name'] == 'South America', 'longitude'] = -57.6561111111

print_full(continental_data)

Step 10: Leave the transforming behind, and move on to the daunting task of generating an animated bubble map.

I wish I could say the hard part is over, but really this is where you need to start paying attention if you ever want to be able to do this in the future without a lot of arm waving and screaming.

At this point we have our dataset. It contains everything we need, continental data per day, location co-ordinates, the whole shebang.

That’s between 33% and 50% of the recipe, now for the final few ingredients.

What do we need to make an animated data visualisation?

Since we want to end up with an animated bubble map, we need to take a slightly different approach than we have previously. Instead of calling the subplots method, we’re going to define our own figure dictionary.

A figure needs 3 things in order to function in a graph_object later on.

- An array of data

- A layout dictionary

- An array of frames

Before we look at some code, let me break down what each of these will contain.

Data array

This is where we define what type of information will be displayed. Meaning things like what type of graph are we creating, or information that’s common to every frame of our final animated bubble map. This information could be the location of the co-ordinates for each continent, the labels assigned to each bubble on the bubble map, etc.

Layout dictionary

This is where we define options such as the title, axes, labels, colours, etc. Similar to the optional arguments we used earlier.

Frames array

This is where we define each and every frame that will make up our animated data visualisation, and in this case each frame will contain the data for a single day in our dataset.

If you’ve heard the term frames per second, or understand the idea behind stop motion animation, then you should understand what this array is, and how it will be used.

And back to our regularly scheduled programming. Data visualisation generation.

Step 10 continued: Generate that bubble map!

So we’ve declared the basic outline of our animated data visualisation. Now let’s start to fill it up.

The first thing we need to do, is to decide what the bubble map will look like when it first loads. Some might argue that it should show the very first day in the dataset, some might argue the very last day, and I’m sure some of you would like to watch the world burn and choose a random day in the middle.

I chose the latest day for which we have data, as this will provide the most up to date information at a glance.

figure = {

'data': [],

'layout': {},

'frames': [],

}

initial_display_day = datesAsStrings[-1]

chart_data = continental_data[continental_data['date'] == initial_display_day]

Step 11: Populate the data array within our figure.

So we have a rough idea of what our visualisation needs to show us, so let’s pick out the elements that are common to every frame of the visualisation, or in other words, lets identify the information that won’t change, no matter what day we decide to look at.

Here’s a list of things that I indentified as being unchanging throughout the animation:

- visualisation type

- co-ordinates for each continent

- the continents themselves

- the basic shape/size/style of the bubbles

- the basic contents of the labels for each bubble

I won’t go into full detail about each line of code, as I think they’re relatively self explanatory, and there are some commentes that should help you figure out some lines of code.

Note: The use of dict() and list() throughout this next section is purely to avoid having to remember the syntax for dictionaries and lists, while keeping syntax highlighting the same throughout to make it easier to read.

for i, cont in enumerate(chart_data['Continent_Name'].unique()):

colour = colour_map[cont]

df_sub = chart_data[chart_data['Continent_Name'] == cont].reset_index()

data_dict = dict(

type='scattergeo',

lat=df_sub['latitude'],

lon=df_sub['longitude'],

marker=dict( # dictionary defining parameters of each marker on the figure

size=df_sub['New_cases'] / 50, # the size of each marker

color=colour, # the colour of the marker

line_color='#ffffff', # the outline colour of the marker

line_width=0.5, # the width of the marker outline

sizemode='area'), # how the size parameter should be translated, area/diameter

name='{}'.format(cont), # series name (appears on the legend)

text=[ # define what appears on the label for each country in the series

'{}<BR>New Cases: {}'.format(

df_sub['Continent_Name'][x],

df_sub['New_cases'][x]) for x in range(

len(df_sub))])

figure['data'].append(data_dict)

Step 12: Time to make some frames.

We’ve built our data array, and filled it with everything we’ll need, so now it’s time to move onto the frames themselves. These will contain every single image that makes up our animated bubble map. Ironically, each frame also requires a data array, so you will notice some duplication of our earlier code.

frames = []

steps = []

for day in datesAsStrings:

chart_data = continental_data[continental_data['date'] == day]

frame = dict(data=[], name=str(day))

for i, cont in enumerate(chart_data['Continent_Name'].unique()):

colour = colour_map[cont]

df_sub = chart_data[chart_data['Continent_Name'] == cont].reset_index()

data_dict = dict(

type='scattergeo',

lat=df_sub['latitude'],

lon=df_sub['longitude'],

marker=dict(

size=df_sub['New_cases'] / 50,

color=colour,

line_color='#ffffff',

line_width=0.5,

sizemode='area'),

name='{}'.format(cont),

text=[

'{}<BR>New Cases: {}'.format(

df_sub['Continent_Name'][x],

df_sub['New_cases'][x]) for x in range(

len(df_sub))])

frame['data'].append(data_dict)

figure['frames'].append(frame)

Step 13: Define the animations via steps.

How do we actually animate between frames? Well that’s where steps come in, each step is like adding animations between slides in a power point. We define the type of transition, the duration, the mode, and the method, and then make sure that the step is attached to a frame and then add it to a step array, which will control how our animation works.

step = dict(

method="animate", # how the transition should take place - should the chart be redrawn?

args=[

[day], # should match the frame name

dict(frame=dict(duration=100, # speed and style of the transitions

redraw=True),

mode="immediate",

transition=dict(duration=100,

easing="quad-in"))

],

label=day, # name of the step

)

steps.append(step)

Step 14: Provide a handy slider so users can go to a specific frame.

Since our animation will be made up of, in this case, hundres of frames, it’s usually best to provide some way for our audience to control what frame they’re looking at. If you don’t want them to be able to go directly to a single frame, you can skip this step.

# changes the sliders at the bottom of the plotted graph

sliders = [dict(

x=0.1,

y=0,

active=len(datesAsStrings) - 1,

currentvalue=dict(prefix="",

visible=True,

),

transition=dict(duration=300),

pad=dict(t=2),

steps=steps # the list of steps is included here

)]

Step 15: Create the layout of the bubble map.

We’re nearing the end of our journey to create an animated bubble map, all that’s left is to actually define what the bubble map will look like. This is where we’ll define the title, the style of the bubble map, add in our previously defined sliders, and add a play/pause button to allow for user control.

# changes title options

title_font_family = 'Arial'

title_font_size = 14

# assigns layout options to the original figure key

figure['layout'] = dict(

titlefont=dict( # parameters controlling title font

size=title_font_size,

family=title_font_family),

title_text='<b> New COVID-19 Cases </b> <BR>', # Chart Title

showlegend=True, # Include a legend

geo=dict( # parameter controlling the look of the map itself

scope='world',

landcolor='rgb(217, 217, 217)',

coastlinecolor='#ffffff',

countrywidth=0.5,

countrycolor='#ffffff',

),

updatemenus=[ # Where a 'play' button is added to enable the user to start the animation

dict(

type='buttons',

direction='left',

x=0.1,

y=0.075,

buttons=list(

[

dict(

args=[

None,

dict(

frame=dict(

duration=200,

redraw=True),

mode="immediate",

transition=dict(

duration=200,

easing="quad-in"))],

label="Play",

method="animate"),

dict(args=[

# Notice the use of [None] vs None. One is pause, one is play. Thanks Plotly & Python ...

[None],

dict(

frame=dict(

duration=0,

redraw=True),

mode="immediate",

transition=dict(

duration=0,

easing="quad-in"))],

label="Pause",

method="animate")

]

)

)

],

sliders=sliders) # Add the sliders dictionary

Step 16: Create the bubble map, and show it off!

These steps should look pretty familiar, but we’re basically just using our figure dictionary to create a graph_object, which we will then show off just like all our previous graphs. The only difference is the final step, which instead of creating a PNG file, it will write the graph to HTML so that it can be included in things like this blog, and still be animated.

# generate the plotted graph

new_covid_cases_bubble_map = graphObject.Figure(figure)

# display the plotted graph

new_covid_cases_bubble_map.show()

# save the plotted graph as HTML code for embedding on websites, without need to host it, and include plotly.js via CDN

new_covid_cases_bubble_map.write_html("./interactive_bubble_map.html", include_plotlyjs="cdn")

Here is where I usually show off the resultant map, inline via an image. However with the animated bubble map, I’ve put it on it’s own separate page to save loading times and your precious RAM.

Click here to see the animated bubble map

The full python script file is available here

Step 17: Gaze upon what you have created, and bask in the glory of a job well done.

That’s it, you’re done. If you made it this far then congratulations. I realise this blog post was infinitely longer than the first, but by now you should know the basics and have an understanding of how to make a more complex data visualisation.

Thank you for reading this blog

Well according to sublime text, this blog post is now over 6200 words. So thank you for your patience, and sticking with me through our journey of learning about how to create data visualisations in python.

References

[1] Plotting the Pandemic with Python and Plotly by Rachel Lund

Disclaimer

All written content is my own work product. I do not claim to be an expert, and cannot guarantee that the opinions within this blogpost are 100% correct.

Acknowledgements

Big thanks to Julian Kapronczai for putting up with my moaning during the process of writing this blog.

Big thanks to Gavin, Eileen, & Philippa Hill for their help with proof reading and being a sounding board for my writing approach.